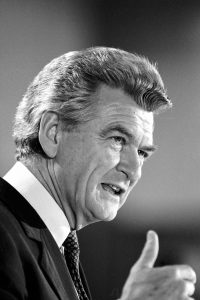

This a meditation on decency, humanity and grace. A eulogy to Bob Hawke who transformed Australia, helped to end apartheid in South Africa, constructed Medicare, built a modern Australian economy and believed that a winner-takes-all approach to politics created losers all round.

It is a personal story so bear with me. And I must give a language warning too.

It was a colourful time. Years ago I worked as an economics adviser to ministers in the Hawke and Keating governments. It was a heady time. The government was tackling structural problems deeply entrenched in the Australian economy in the belief that a more productive economy provided a means for a better life. I was ambitious and the breadth of government ambitions inspired me. I thought—I still think—I was contributing to a better world.

At the time, a friend of mine was working in a special-needs school in Sydney. More a therapist than a teacher, she had in her care teenage boys who had profound behavioural problems. They weren’t bad but on a bad day they were rascals: dysfunctional, abusive, obscene, unruly, uncooperative and surly. They perceived themselves as having no worth and no hope, and they defined themselves, very often, by being slow to respond and quick to resist.

Like many students they came down to Canberra on a tour. Civics. The War Memorial and Parliament House. The usual sort of thing.

I didn’t know anything about teenagers or that sort of stuff but when they came to Parliament House as a group we wandered around empty halls and across polished wooden floors. One observed that the place ‘must’ve cost a fuckload of shit’.

Earlier that day, I’d mentioned to Craig Emerson, who was an adviser to Bob Hawke at the time, that I was shepherding a group around and would be keen to just look at the prime minister’s office. At a distance. Or, if the federal coppers allowed, perhaps go through the front entrance of the office and into the office itself and gawk.

We were wandering up and down the corridors of a busy Press Galley when a message arrived. Cabinet had taken a break. The prime minister was having ten minutes to himself and would be very happy to see us.

The boy who was so critical about halls and floors told me that I’d better not be telling him a fuckload of shit or, or, or, fuck I’d just better fucking not.

Bob Hawke met us in the alcove that led to his private office. He was at his relaxed best even though, ten minutes ago he had been chairing a meeting of very smart ministers and deciding, perhaps, on the future of Commonwealth–state relations or whether or not tariffs should be reduced. Or whether the navy base in Jervis Bay should be expanded to monstrous size.

He spoke clearly and warmly to each of the gang of three. He brought them into his office and he asked them what they thought and he listened to what they said and he had the prime ministerial butler bring in sparkling water in prime ministerial glasses. He spoke about the job and what he loved about it and what was difficult and he touched each of them and proved that they actually mattered. A Cabinet officer brought in the message that ministers were back and Bob Hawke kept his ministers waiting.

He said that Australia was a fantastic country and people like them had built it, and that they were never to short-change themselves or believe they weren’t up to the mark. He breathed confidence into them. He proved they were worthy.

He asked them if they had any questions.

And one asked if he could sit in the prime ministerial chair behind the prime ministerial desk. And the prime minister said you could sit there one day for real if you really gave it a crack. In this country you can do that.

So while Cabinet waited, the three of them took turns trying out the chair for size. They stood close together, nestled up to Bob Hawke who from the middle of the group stretched out his arms and enveloped them all in his easy, comfortable embrace. It was a fantastic moment, three young guys relaxed, unified and happy. Perhaps for a moment believing their luck had changed. Perhaps believing in the possibility of a chance. Bigger for a moment because of the care and interest lavished on them by their prime minister.

Later I heard that on telling the story to his father, one had been given a hiding for being ‘a dirty, lying little bastard’. And even later, I heard that his father had drunken sobbed after being shown the photo of his son, with his friends and Bob Hawke.